Bamboo History Timeline: From Ancient Traditions to Modern Innovation

In this comprehensive bamboo history timeline, you’ll find key milestones, inventions, and cultural shifts that highlight how bamboo evolved from a humble grass into a material at the forefront of sustainable design and innovation. Whether you’re interested in architecture, ecology, technology, or cultural heritage, this timeline reveals why bamboo remains one of humanity’s most valuable renewable resources.

5500-3300 BC | Hemudu Culture and the Earliest Preserved Matting and Basketry in China

The Neolithic Hemudu culture of Zhejiang, China, is among the first archaeological contexts worldwide where woven plant materials have been directly preserved. Due to the waterlogged conditions of the Hemudu site, archaeologists recovered reed mats, basketry, and other plant-fiber objects dating back more than 7,000 years.

These finds provide rare insight into how early communities used reeds and bamboo-like plants for floor coverings, household furnishings, and everyday tools, showing that weaving and matting traditions in East Asia stretch back deep into prehistory. The Hemudu discoveries not only confirm early plant-fiber technology but also hint at the beginnings of the sophisticated bamboo and reed weaving industries that would later define Chinese material culture.

Sources:

3500-1500 BC | Earliest Evidence of Bamboo-Style Dwellings in Coastal Ecuador

Archaeological excavations of the Real Alto site of the Valdivia culture have uncovered pottery and settlement remains that some researchers interpret as representing wattle-and-daub or “bahareque”-style dwellings, likely incorporating bamboo or similar cane materials. These depictions suggest that early coastal societies may have experimented with bamboo construction techniques thousands of years ago, forming part of a long tradition of vernacular architecture in the region.

However, the evidence is indirect: stylized pottery motifs cannot confirm bamboo specifically, and the continuity of guadua and cane-based building traditions in coastal Ecuador today highlights the need for caution when linking modern practices directly to these earliest sites.

Sources:

c. 2200 BC | Bamboo Instruments in China’s “Eight Sounds” (Bāyīn) System

In early Chinese tradition, musical instruments were classified according to the “Eight Sounds” (bāyīn, 八音) system, which grouped instruments by the material of their construction: stone, metal, earth (clay), skin, silk, wood, gourd, and bamboo. Bamboo instruments, especially flutes and pipes, were closely associated with ritual and seasonal symbolism, reflecting bamboo’s deep cultural role in early Chinese life.

Some classical sources even attribute the origins of the system to the legendary Emperor Shun (traditionally dated to 2225–2206 BC), though this should be understood as mytho-historical tradition rather than precise historical record. Regardless of its exact date of origin, the bāyīn classification highlights how bamboo became integral to music, ritual, and philosophy in ancient China, long before formal dynastic histories were written.

Sources:

256 BC | Bamboo in the Dujiangyan Irrigation System (China)

The Dujiangyan irrigation system, constructed in 256 BC under the leadership of engineer Li Bing, remains one of the world’s oldest functioning hydraulic projects. To divert and regulate the Min River, workers used a combination of timber, stone, and woven bamboo structures, such as gabions and temporary frames, to build the initial dikes, stabilize embankments and guide water flow.

This use of bamboo in large-scale hydraulic engineering highlights its role not only in daily life and architecture, but also in state-level infrastructure projects of the Qin period. Today, Dujiangyan is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, still operating on its original principles more than 2,000 years later.

Sources:

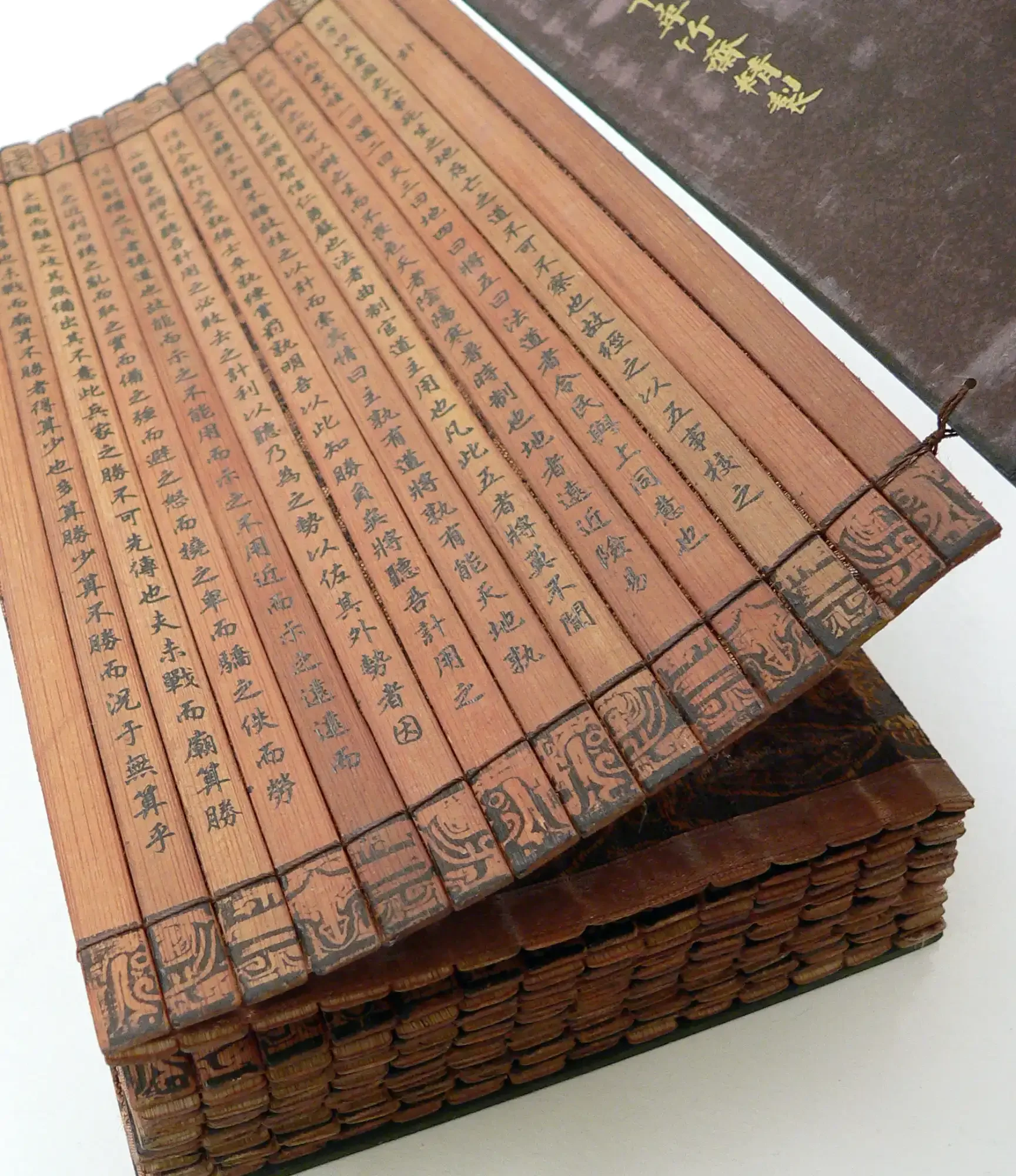

281 AD (and Earlier) | Bamboo Slips Preserve Ancient Chinese Texts

Bamboo and wooden slips were a principal writing medium in ancient China long before paper became widespread. The earliest surviving examples date from the Warring States period (5th century BC onward), including philosophy, administrative records, and poetry inscribed on bundled strips.

These discoveries from archaeological contexts such as Guodian tombs (~300 BC), Jizhong cache (279 AD), and Shuihudi slips (217 BC) form the bedrock of early Chinese historiography and literary study. While references in ancient texts hint at even earlier usage (late Shang narrative traditions), no verified physical examples have survived from that era to confirm actual practice.

Sources:

3rd Century AD | Laminated Composite Bows: Bamboo/Wood, Horn, and Fish-Glue Adhesive Innovations

Historical and archaeological evidence affirm that laminated composite bows featuring wooden or bamboo cores reinforced with horn (on the belly) and sinew (on the back) all bound with adhesives like fish-bladder glue, were widely used across Eurasia, including China, from ancient times through the third century AD.

The mechanical design allowed these bows to store more energy than self-wood alternatives, delivering high draw weight, shorter length, and increased power, especially advantageous for mounted archers.

Chinese archaeological finds confirm such laminated bows existed as early as the Spring and Autumn period (770–476 BC), becoming a staple through the Han and Jin dynasties. While such bows could outperform many wooden designs, claims that they were “stronger than any metal” are overstated; they were sophisticated in energy storage and efficiency, not literally stronger than metal.

Sources:

552–563 AD | Byzantine Silk Smuggled via Bamboo Canes

According to the 6th-century historian Procopius, during Emperor Justinian I’s reign (527–565 AD), two Nestorian monks smuggled silkworm eggs or larvae into the Byzantine Empire, widely believed to have concealed them inside hollow bamboo walking sticks. Locking in control over silk production, this mission ended Persia’s monopoly and sparked the rise of a native Byzantine silk industry in cities like Constantinople, Beirut, and Antioch. While timelines vary, estimates place the event between 552 and 563 AD, fitting with Procopius’s near-contemporary account and supporting historical consensus.

Sources:

c. 1050–1100s AD | “Great Well of China”: Early Deep Brine Drilling with Bamboo Tubing in Sichuan

By the early 11th century, engineers in Sichuan’s Jingyan district had innovated deep rotary drilling systems using flexible bamboo “cable” tubing instead of solid casings. This lighter, more adaptable design allowed wells to reach greater depths (hundreds of meters) with far less mechanical stress, revolutionizing well engineering.

By the Song dynasty, bamboo-assisted drilling became critical to the region’s salt extraction economy; by the 18th century, wells typically reached 300-400 meters, and in 1835, the Shenghai Well topped 1,000 meters, setting a global record. This technological advance predated similar European techniques by centuries and highlights China’s early mastery of deep drilling methods.

Sources:

1486 | Development of Bamboo Charcoal in China

Documentary evidence from Ming Dynasty China (as early as 1486) attests to the production and use of bamboo-derived charcoal. Unlike traditional wood or mineral coal, bamboo charcoal was valued for its highly porous microstructure, which enhanced combustion efficiency and reduced smoke emissions. The process typically involved carbonizing mature culms (≥ 5 years old) at elevated temperatures (ca. 600–1,200 °C).

Beyond its role as a cleaner fuel, bamboo charcoal also found applications in filtration, humidity control, and medical preparations. These records illustrate an early awareness of bamboo’s environmental and technological potential, positioning bamboo charcoal as one of the earliest documented examples of sustainable material innovation in pre-modern China.

Sources:

1492–1493 | Columbus Encounters New World Bamboo

During his first voyage to the Americas, Christopher Columbus reported encountering “canes as thick as the leg of a man.” This early European description of massive tropical grasses (possibly Guadua angustifolia or another giant cane) astonished Columbus and his crew, who compared them more to trees than to grasses.

Even before Columbus’s voyage, bamboo culms drifting across the Atlantic had been noted in Europe without a known source. Columbus’s observations helped link these mysterious specimens to the Americas, indirectly contributing to early knowledge of the Gulf Stream, which would later become vital for navigation between Europe and the New World.

Sources:

1753 | Linnaeus Introduces Bamboo into Scientific Nomenclature via Arundo bambos

In his landmark work Species Plantarum (1753), Carl Linnaeus formally classified a bamboo species as Arundo bambos, which marked bamboo’s first inclusion in the modern system of botanical taxonomy. Although this genus placement was later revised, the initial naming laid the groundwork for bamboo’s scientific recognition. Today, the species is known as Bambusa bambos, but the original nomenclature remains a key milestone in botanical history.

Sources:

1792 | George Cayley’s Rotorcraft Concept Inspired by Chinese Bamboo Toys

In the late 18th century, English engineer George Cayley (known as the “father of aviation”) conducted early rotorcraft experiments using models inspired by the ancient Chinese bamboo-copter, a helicopter-like toy from the Jin Dynasty (~320 AD). Using bow drills and rotating propellers made from cork and feathers, Cayley created “rotary wafts” that explored vertical flight dynamics.

While the connection between the toy and his experiments is conceptual rather than direct, it illustrates how simple mechanical curiosities helped spark foundational ideas in aeronautical engineering.

Sources:

1816–1824 | Father Diego Cera Builds the Unique Las Piñas Bamboo Organ

Starting in 1816, Father Diego Cera de la Virgen del Carmen, parish priest of Las Piñas, began constructing a one-of-a-kind pipe organ made largely from bamboo. Over eight years of craftsmanship, he carefully rammed and selected bamboo (Bambusa species) buried under sand to ensure quality and resilience, completing the organ in 1824. With 1,031 pipes, 902 of which are bamboo, the instrument remains fully functional and is celebrated as the only bamboo organ in the world. It stands today as a symbol of cultural fusion, musical innovation, and the lasting heritage of Philippine craftsmanship.

Sources:

1826–Late 19th Century | Bamboo Enters Western Gardens through Botanical Exploration

Starting in the early 19th century, botanical gardens across Europe and North America began introducing Asiatic and American bamboo species, including Phyllostachys, Bambusa, and Arundinaria. For instance, Kew Gardens received its first bamboo (Phyllostachys nigra) in 1826, marking the beginning of a surge in bamboo collecting and cultivation for scientific, ornamental, and exotic interests. This horticultural wave accelerated as plant hunters and garden enthusiasts transported specimens across continents, laying the foundation for the diverse bamboo collections seen today in arboreta and botanical institutions worldwide.

Sources:

1876 | Alexander Graham Bell’s Early Phonograph Used a Bamboo-Tipped Needle

During the pioneering era of sound recording, Alexander Graham Bell and other experimenters occasionally used natural materials to construct phonograph components. In at least one documented account, Bell employed a sharpened bamboo sliver as the needle in his early phonograph, a practical choice due to bamboo’s suitability for fine, replaceable tips.

While this example is often cited in modern discussions of material ingenuity, contemporary primary documentation is sparse, so it remains plausible but not conclusively confirmed in every detail.

Sources:

1878–Late 1880s | Edison’s Use of Carbonized Bamboo Filaments in Early Incandescent Bulbs

Thomas Edison’s research team at Menlo Park experimented with thousands of materials to find a durable, high-resistance filament. By the late 1870s to mid-1880s, carbonized bamboo, particularly from species like Phyllostachys bambusoides, became the preferred filament in many of Edison’s incandescent lamps.

Remarkably, these bamboo filaments achieved lifespans of over 1,200 hours, far outlasting earlier cotton or wood options and becoming the dominant filament choice before tungsten took over. An actual Edison bamboo-filament lamp from around 1880 survives in museum collections, underscoring its historical importance.

Sources:

1894 | First Patented Bamboo Bicycle in England

In 1894, the Bamboo Cycle Company Ltd in England introduced and patented the first bamboo-framed bicycle. It was unveiled to the public on 26 April 1894 at the London Stanley Cycle Show and quickly became a sensation. This marked the first official recognition of bamboo’s potential in bicycle design, leveraging its natural strength, flexibility, and shock-dampening qualities. The innovation set a precedent for sustainable bicycle construction, though large-scale adoption would be delayed by the rise of steel and aluminum frames.

Sources:

c. 1900 | Edison’s Bamboo-Reinforced Cement Pool in Florida

At his winter estate in Fort Myers, Thomas Edison reportedly used bamboo poles instead of steel rebar to reinforce the foundation of his residential swimming pool, constructed around 1900–1910.

Although Edison’s estate was known for its experimental construction materials including Edison Portland Cement, the claim about bamboo reinforcement comes primarily from local historical accounts and estate lore, rather than rigorous engineering documentation.

Despite its anecdotal nature, the pool’s longevity and the consistency of these reports make it a plausible but not fully substantiated example of early bamboo engineering innovation.

Sources:

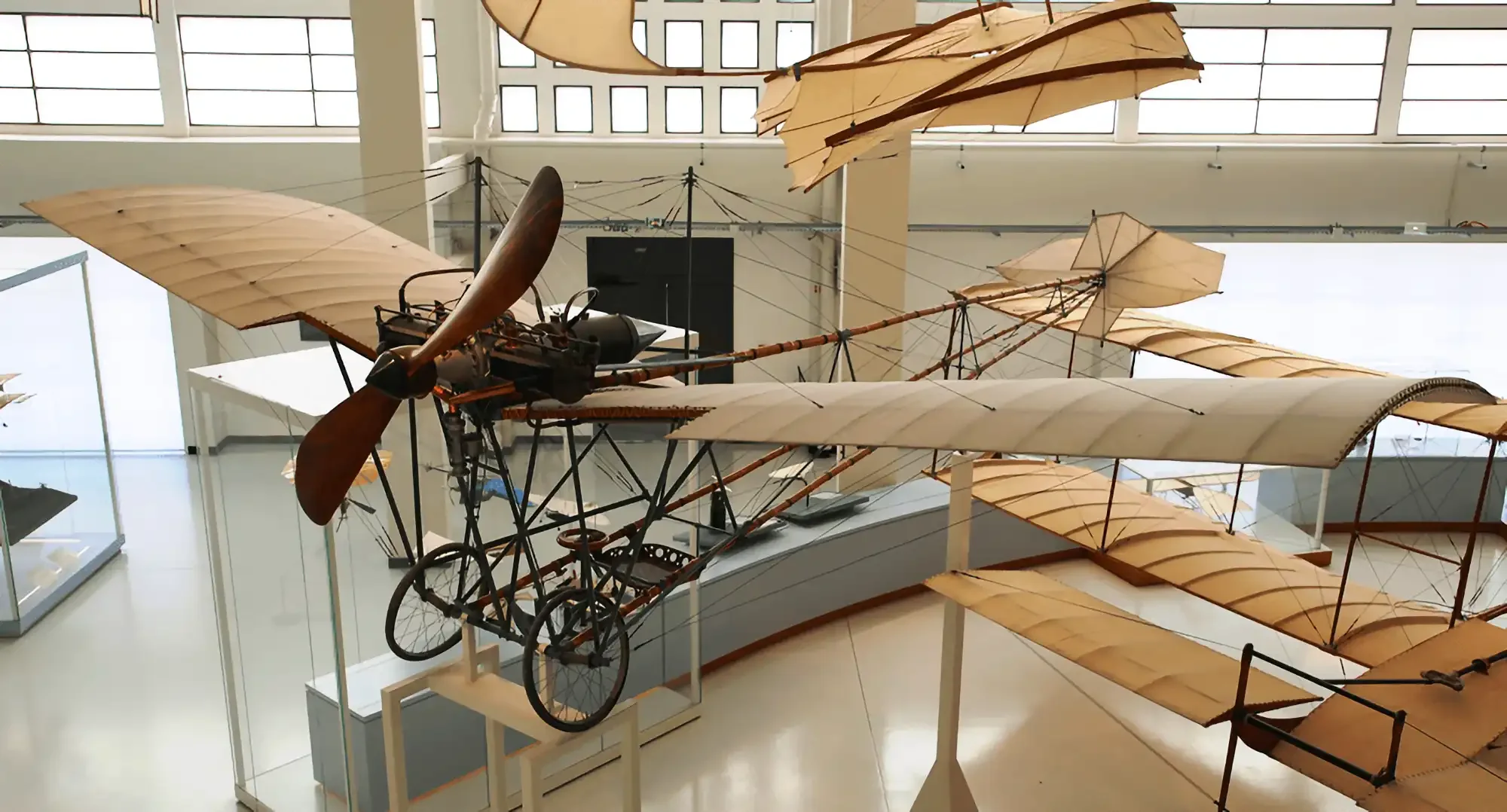

1901–1906 | Santos-Dumont’s Bamboo-Structured Dirigible and Demoiselle Aircraft

Between 1901 and 1906, Brazilian aviation pioneer Alberto Santos-Dumont achieved groundbreaking feats in early flight. His No. 6 dirigible circled the Eiffel Tower in 1901, while his Demoiselle monoplane, one of the first factory-produced light aircraft, featured a lightweight framework, including primary bamboo longerons connected by steel and brass, with wings incorporating bamboo ribs and ash spars affording both structural strength and minimal weight. These designs underscore bamboo’s pivotal role in pioneering aviation history.

c. 1917 | Reported Use of Bamboo in Temporary Japanese Railroad Trestles

Regional engineering histories from early 20th-century Japan note the use of bamboo scaffolding and temporary trestles in challenging terrains during railway expansion. While bamboo was widely used in vernacular construction, authoritative records confirming bamboo trestles from 1917 are scarce online. Concrete confirmation may exist in Japanese technical archives or local museum collections but is not yet accessible through broad web sources. For now, this remains a plausible but unverified component of early railway engineering in Japan.

Sources:

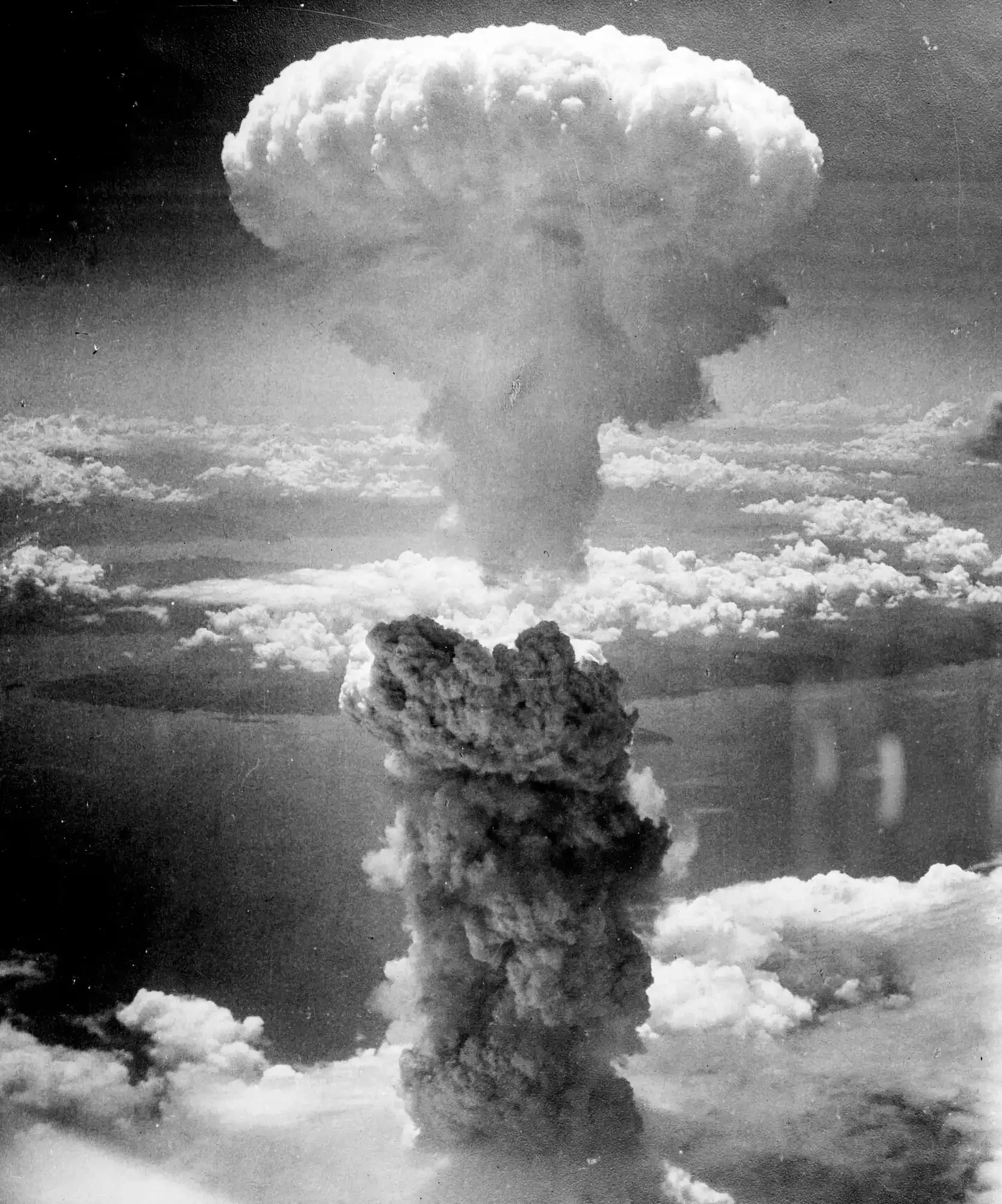

1945 | Bamboo Included Among Hiroshima’s “Hibakujumoku” (Survivor Trees)

Hibakujumoku, or survivor trees, are plant species that miraculously endured the Hiroshima atomic bombing in 1945 and re-sprouted in the years that followed.

Among them, members of the bamboo tribe (Bambuseae) are listed in botanical registries as part of the resilient flora that have become living symbols of recovery. These trees (including bamboo) are recognized as natural memorials that demonstrate extraordinary biological resilience and are formally preserved as part of Hiroshima’s Peace Park and educational programming.

Sources:

1947 | Gucci Introduces the Iconic Bamboo-Handled Handbag

Due to material shortages after WWII, Gucci designers improvised by crafting handbag handles from bamboo. Each handle was carefully heated and bent over an open flame, then sealed with lacquer for strength and durability.

The Gucci Bamboo Bag, introduced in 1947, quickly captured the fashion world, embodying resilience, elegance, and artisanal craftsmanship. Beloved by style icons such as Ingrid Bergman, Elizabeth Taylor, and later Princess Diana and Beyoncé, the bag became an instant classic. Its success led Gucci to patent the bamboo handle in 1958, ensuring the unique design could not be copied.

Today, the Bamboo Bag remains a symbol of Gucci’s creativity and innovation. It continues to appear in the brand’s signature collections and stands as an enduring example of bamboo’s versatility and luxury appeal.

Sources:

1950s | Bamboo Woven Composite (“WOBEX”) Used in Philippine Experimental Aircraft

In the early 1950s, engineers at the Institute of Science and Technology (formerly the Bureau of Science) in Manila pioneered the use of WOBEX, a woven bamboo composite, for lightweight stress-skin panels in aircraft. The I.S.T. XL-14 Maya (circa 1953) featured a fuselage utilizing this technology, and its successor, the I.S.T. XL-15 Tagak (mid-1950s), continued the experiment in utility aircraft design.

Materials testing from the period indicates that these bamboo-panel composites achieved fatigue strength superior to conventional wood, with bonding between bamboo layers comparable to bamboo-to-wood adhesion. These prototypes represent a rare and fascinating example of bamboo’s integration into mid-20th-century aeronautical engineering.

Sources:

1979 | Founding of the American Bamboo Society Marks Organized Bamboo Advocacy in the U.S.

Established in 1979 by a small group of bamboo enthusiasts, including Richard Haubrich, the American Bamboo Society (ABS) began as a regional organization that quickly grew into a national hub for bamboo growers, designers, hobbyists, and researchers. Initially based at Quail Botanical Gardens in California, ABS became incorporated in 1981 and has since helped introduce new bamboo species, disseminated practical cultivation knowledge, and fostered community through publications and local chapters across the U.S. Its formation represents the first sustained, organized effort to promote bamboo’s ecological, horticultural, and cultural value in America.

Sources:

1980s | Bamboo Flowering Crises Spark Global Pandamonium

In the 1970s and 1980s, large-scale synchronous flowering of bamboo in China’s Minshan and Qionglai Mountains caused widespread die-offs of key bamboo species. This triggered food shortages that were credited with the deaths of over 200 giant pandas, thrusting bamboo ecology into the international spotlight. These catastrophic events underscored how bamboo’s infrequent, mass-flowering cycles could endanger ecosystems and species survival, galvanizing global conservation discourse and media attention around the “pandamonium” of nature’s boom-and-bust rhythm.

Sources:

1980s | China Pioneers Laminated Bamboo Flooring

In the late 1980s, China pioneered the industrial production of laminated bamboo flooring, representing a significant advance in the field of engineered bamboo materials. This development transformed bamboo from a primarily traditional construction resource into a standardized, globally marketable product. The process—comprising the cutting of culms into strips, removal of the outer cortex, and subsequent lamination under heat and pressure—produced flooring boards with mechanical properties comparable to conventional hardwoods.

By the 1990s, production expanded rapidly, supported by technological refinements and export-oriented industrialization. Laminated bamboo flooring not only provided a durable and sustainable alternative to tropical hardwoods, but also positioned bamboo as a competitive material in global flooring markets, foreshadowing the later diversification of engineered bamboo composites.

Sources:

1990s | Tissue Culture Methods for Bamboo Propagation

During the 1990s, advances in plant biotechnology led to the successful establishment of tissue culture techniques for bamboo propagation. These in vitro methods enabled large-scale clonal multiplication of elite genotypes, overcoming the species’ long flowering cycles and seed scarcity. The technology has since supported both industrial applications (e.g., plantation establishment for timber and biomass) and conservation programs, by preserving genetic resources of threatened species. Tissue culture became a foundational tool for ensuring reliable, uniform, and sustainable bamboo supply.

Sources:

1993 | Tim Severin’s Hsu Fu Bamboo Raft Expedition (Experimental Archaeology)

Explorer and author Tim Severin launched the Hsu Fu, a 60-foot bamboo raft, from Hong Kong in 1993 to test theories of ancient Chinese seafaring. The voyage was an experimental reconstruction based on accounts of Emperor Qin Shi Huang’s envoy, Xu Fu, who was said to have sailed eastward in search of the elixir of life in 218 BC. Severin’s expedition demonstrated both the strengths and limitations of bamboo rafts in long-distance navigation across the Pacific. The journey was later documented in his 1994 book The China Voyage.

Sources:

1997 | INBAR (International Bamboo and Rattan Organization) Established as an Intergovernmental Organization

In 1997, the International Bamboo and Rattan Organization (INBAR) was formally established as the first intergovernmental organization dedicated to promoting bamboo and rattan for sustainable development. The organization was born from efforts initiated in the mid-1990s and gained momentum through a foundational agreement signed on 6 November 1997 in Beijing, with founding member states including Bangladesh, Canada, China, Indonesia, Myanmar, Nepal, Peru, the Philippines, and Tanzania. INBAR evolved from a researcher network into a global organization supporting environmental resilience, poverty alleviation, and eco-innovation.

Sources:

2000 | Simón Vélez’s Guadua Pavilion at Expo Hanover Showcases Engineered Bamboo Architecture

In 2000, Colombian architect Simón Vélez designed and constructed the ZERI Pavilion (Zero Emissions Research Initiative) at Expo Hanover. The 2,000-square-meter structure built from Guadua bamboo, recycled cement, copper, terracotta, and bamboo fiber panels, earned international acclaim as the first bamboo structure in history to receive a building permit in Germany and was the most visited pavilion of the Expo. Vélez’s innovative work helped cement bamboo’s reputation in contemporary architecture and influenced global conversations around sustainable building codes.

Sources:

2002 & 2010 | Colombia Codifies Engineered Bamboo in National Building Codes

Following the devastating 6.2 magnitude Quindío earthquake in 1999, bamboo (bahareque) houses proved remarkably resistant to seismic forces. In response, the Colombian Association of Structural Engineers (AIS) launched detailed studies on the mechanical behavior of Guadua bamboo. These efforts led to the 2002 recognition of mortared bahareque (bahareque encementado) as an approved structural system within NSR-98, Colombia’s seismic-resistant construction code.

A major milestone followed in 2010 with NSR-10, which introduced Chapter G.12, the world’s most comprehensive standard for engineered Guadua bamboo structures. This chapter established design values for beams, columns, and connections, as well as safety factors for round bamboo culms, providing a robust framework for modern bamboo construction.

Sources:

2021 | ISO 22156: Structural-Design Standard for Bamboo Culms Issued

In 2021, ISO released its second edition of ISO 22156, providing the first international structural design standard specifically for round bamboo culms. This standard offers reference values and design parameters for load-bearing bamboo buildings up to two stories—codifying global best practices for bamboo construction. Its publication marks a critical milestone in elevating bamboo from vernacular use to regulated, international-quality engineering.

Sources:

The story of bamboo is still unfolding. What began with simple tools, arrows, and baskets has grown into a global movement toward sustainable living and innovative design. From ancient dynasties to modern laboratories, bamboo continues to prove its strength, beauty, and ecological importance.

By understanding the history of bamboo, we gain insight into its future: a world where renewable materials like bamboo may hold the key to addressing climate change, sustainable housing, and eco-friendly technologies. Explore our related guides on bamboo architecture, cultivation, and modern applications to continue your journey into the world of bamboo!